The fields and forests northwest of Verdun, bordered by the Meuse River on the east and the Forêt d’Argonne on the west, were the scene of the most intense fighting experienced by American forces during the First World War. The engagement raged from 26 September to 11 November 1918 and, because of the geography, became known as the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. The combined French / American offensive was successful and contributed to the Germans seeking the Armistice which ended the war on 11 November.

Fighting northward through Varennes-en-Argonne, the Americans confronted a series of strong German defensive lines, or Stellung, given the names Hagen, Giselher, Kriemhilde, and Freya after characters in Wagnerian operas. The third of these was the most extensive and presented attackers with an almost continuous 10-mile belt of machine-gun positions and barbed wire. The terrain provided numerous opportunities for mutually supporting cross- and enfilade-fire and it exposed attackers to shelling from artillery hidden in the forests.

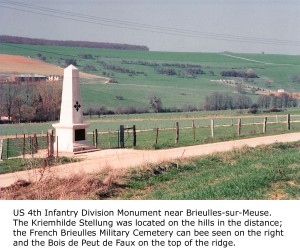

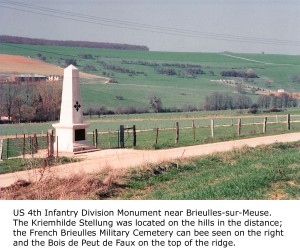

It was mid-spring 2005 and I had been in the area for several days reviewing the sites relating to the battle. On one particular afternoon, I drove the roadways near Brieulles-sur-Meuse to view the Kriemhilde Stellung terrain. Beside the road was a stone monument to the US 4th ‘Ivy’ Infantry Division, which had suffered 7,412 casualties in the brutal local fighting. I wanted a photograph and, contrary to my normal policy of finding a safe, public area to park, I instead turned onto muddy, farm track. After all, it was a quiet afternoon and nobody was about.

Struggling to get a perspective of the monument with the forests and hills of the stellung in the background, I climbed up a 7 foot verge and walked 300 feet or so along it. No sooner had I positioned myself, than I heard the rumble of heavy farm machinery. I knew immediately that it had to be coming down the farm track now blocked by my parked rental car. I hastened along the top of the verge and slipped down the steep incline in time to meet the tractor that had stopped just inches away from the car’s front bumper. I prepared myself for a tongue-lashing in French, or worse. The tractor’s driver stepped out of the cab and climbed down – presenting me with what I thought must be the largest farmer in northern France. Continue reading →

Struggling to get a perspective of the monument with the forests and hills of the stellung in the background, I climbed up a 7 foot verge and walked 300 feet or so along it. No sooner had I positioned myself, than I heard the rumble of heavy farm machinery. I knew immediately that it had to be coming down the farm track now blocked by my parked rental car. I hastened along the top of the verge and slipped down the steep incline in time to meet the tractor that had stopped just inches away from the car’s front bumper. I prepared myself for a tongue-lashing in French, or worse. The tractor’s driver stepped out of the cab and climbed down – presenting me with what I thought must be the largest farmer in northern France. Continue reading →